The role of coroners in Pennsylvania’s opioid epidemic

If the needle never left the arm, it was probably fentanyl.

For the professionals tasked with determining the precise cause of overdose deaths, clues can be found in scarce amounts of powder, bags, syringes, spoons and scales. But one piece of evidence – the body of the victim – reveals more than the rest.

A syringe’s needle still in an arm of a body could point to fentanyl as the drug. It’s up to 50 times stronger than heroin. And bodies have been found with enough to kill six horses.

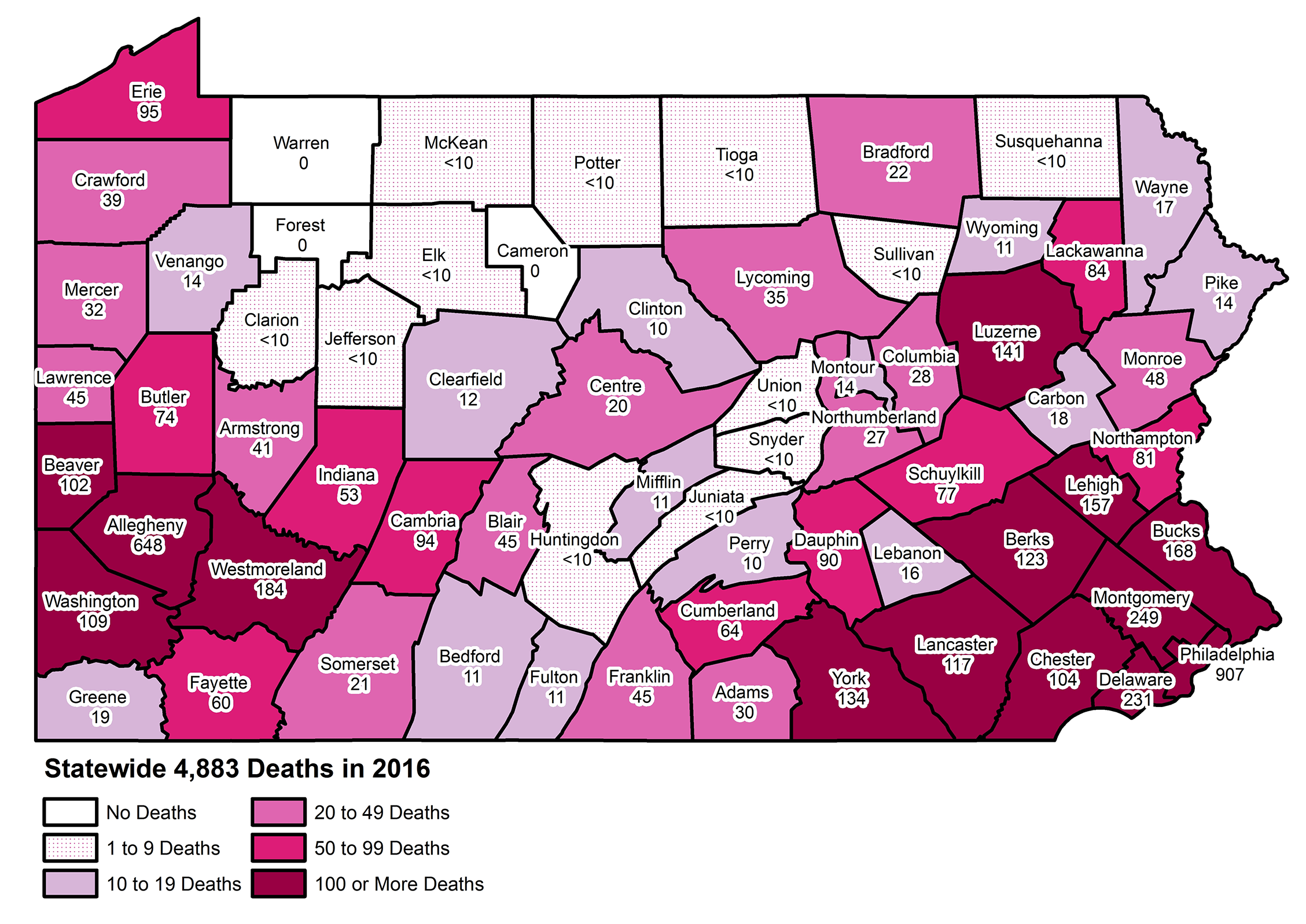

Nearly 13 people die from drug abuse every day in Pennsylvania. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Pennsylvania’s age-adjusted drug overdose death rate, nearly 40 per 100,000 people, is twice as high as the national average. With over 63,600 deaths in the United States in 2016, President Donald Trump has declared the opioid epidemic to be national crisis.

Enlarge

In this epidemic, those who die and their families are the victims. But an ugly toll has also been placed on those whose jobs it is to investigate those deaths.

In each of the 67 counties in Pennsylvania, that task falls to the coroner or medical examiner.

Typical of these professionals is Charles “Chuck” Kiessling, who has held the job in Lycoming County for 18 years. Tucked into a third-floor office in Williamsport, Kiessling spends much of his days chasing papers, glued to the phone, or tethered to his pager. However, he gets called out of his office or his home at all hours of the day, responding to anything from fatal crashes to drug overdoses.

“Our primary goal is to determine cause and manner of death,” he said, looking down from his thinly rimmed glasses, fingers tapping lightly on the desk. “We’re not just body-haulers. We investigate cause and manner of death, and that has to be done correctly, no matter where it’s being done.”

The principal laws in this profession have hardly changed since the 1600s, according to the Pennsylvania State Coroners Association’s attorney, Susan Shanaman. Anything other than a natural death must be investigated by a coroner or medical examiner.

After an overdose death, for example, the body becomes a case for the county’s coroner — an elected, four-year position in most counties. Philadelphia, Delaware and Allegheny have appointed medical examiners, physicians by definition. County coroners can be medical doctors, but they don’t have to be. Some are funeral directors, nurses or firefighters.

Kiessling is also a flight nurse. He said that, in Lycoming County, “we pick up the body as evidence, and we have to maintain that chain of custody from where the death occurred, to our morgue, to Allentown for an autopsy to be completed.”

With a county larger than the state of Rhode Island, Kiessling and two full-time deputies cover 1,244 square miles. Allentown, a two-hour drive away in Lehigh County, is the closest laboratory that Kiessling and his team can have an autopsy performed.

“On TV, they run back to the lab and within two minutes they have all this stuff done,” he said. “That’s not realistic. For us, we have to drive to Allentown, so we transport bodies 144 miles each way for an autopsy.”

With drug deaths up about 30 percent in his county in 2016, Kiessling said his budget was stretched to its limit. He can’t afford to have autopsies completed for every case that hits his desk. Of the 38 drug deaths in his county last year, Kiessling had two autopsies completed.

An autopsy can cost anywhere from $1,800 to $3,800, and that’s not including travel or personnel costs, Kiessling said.

In 2016, his office started using oral-swab samples for toxicology — lab procedures identifying and quantifying potential drugs and toxins.

Tools pack an old yellow cabinet of Kiessling’s Lycoming County morgue. ~ photo by Kelly Powers

The results, which Kiessling hopes to receive within 48 hours, often show lethal doses of 10 or 12 different substances, from heroin, fentanyl, cocaine and carfentanil. And sometimes that’s where the investigation ends.

“At that point, we’re using that to say, ‘OK, that person had lethal blood levels of all these substances,’ and we sign them out,” Kiessling said. “I don’t have the resources to run to and from Allentown with all those cases that are not going to be prosecuted… Who pays for all this stuff?”

Kiessling said these increasingly complicated death investigations put stress on the entire system.

And other coroners report the same problem. Jeremy Reese, the Columbia County coroner, oversees investigations in a county that recorded 28 drug deaths in 2016, about 20 percent of his caseload. He said the most frequent cause of death was strong heroin at first, then it became a mix of heroin and fentanyl, and it is now almost exclusively fentanyl.

Fentanyl, in the form of patches, was given to patients for management of many types of chronic pain. But there has been a steady stream of modifications since. Now fentanyl, a cheaper substitute for heroin on the street, has become a major player in drug overdose deaths.

“There doesn’t seem to be an end in sight,” Reese said. “It gets very repetitive at times, to continue to see these opioid deaths.”

Reese, who once served as EMS chief and assistant fire chief with the Millville Community Fire Company, saw four drug-related fatalities in a matter of about four days this past summer.

“I think a lot of the public, they don’t realize what the coroners do,” he said. “Even I had 20 years in public safety before I became a coroner, and I didn’t realize what was involved… There’s a lot more investigation. There’s a lot more working with families.”

Life is another reality

Kenneth Bacha’s voice quivered slightly as he spoke about his day job. Another of the coroner’s duties is to notify the next of kin.

“How do you deal with these families? The mental and emotional side of it has gotten crazy,” the Westmoreland County coroner said.

Bacha went from 22 drug deaths in his first year in office in 2002 to 184 in about 14 years in his county just outside of Pittsburgh.

“We know these people too, some of them are friends of ours… We know their kids had a drug problem and so on,” Bacha said. The coroner, bags under his blue eyes, began to knock softly on the table in front of him. “And they know, at some point, we’re going to be knocking on their door… I mean, we do identifications all the time, but how do you do it with the people that you know?”

A used syringe rests on the carpet of a Lycoming County residence as Kiessling's office begins to investigate ~ photo courtesy the Lycoming County Coroner's Office

It’s also not strange for Bacha to be approached inside the grocery store or in a restaurant when he goes out to dinner with his family.

“‘Hey, my nephew, I think he has a drug problem, can you tell me?’” Bacha said, eyes widened. “And, my wife goes, ‘Kenny, can’t you get away from this for like five minutes?’”

Back in Lycoming County, Kiessling echoed Bacha, noting that some nights he may think he’s going out with his wife, only to be torn away by his cell phone, smartwatch or pager.

And each case is not like the last. One call, in particular, will always stay with Kiessling.

“It didn’t click for me — where I was going. The address didn’t mean anything,” he said.

It was Super Bowl weekend, 2016.

Kiessling has known Carolyn Miele for 28 years, as she and his wife worked together as nurses at Geisinger Hospital in Williamsport. But he never expected his job to bring him to her house on Pennsylvania Avenue that night nearly three years ago.

Struggling with a difficult relationship but sober for nearly three years, Zachary Bigelow, Miele’s son, had just moved back home. Miele said her 27-year-old was excited to pick up his own son that day from his mother and get back to the house in time for a presidential debate that night.

When Miele got home, she saw the television was set to record the debate. She thought her son must have been sleeping away one of his headaches that had become commonplace. He was to have three impacted wisdom teeth taken out in a month.

“I thought, ‘Oh, I better go up and check on him.’” Miele said, tears filling her eyes. That’s when she found him dead of a heroin overdose.

From there, it’s a blur. “I was just screaming,” she said. “That’s all I can remember. Screaming.”

Miele said she remembers seeing Kiessling when he got to the house. Because he had been a close friend for years, Kiessling abandoned his protocol of assessing the body before speaking with the family. He went straight to Miele.

“Carolyn had talked to me earlier, back around the holidays. She had asked would I be willing to talk to Zach about addiction, and what we’re seeing,” Kiessling said. “But, we never got around to it.”

Miele, talking about the local coroner, said she “can’t imagine doing what he does, because he has to come in and deal with that part of it, the families. That had to have been really hard for him, to have to come to my house.”

Kiessling acknowledged the emotional toll, noting there are other terrible aspects of the job as well. “I’ve been physically assaulted by families,” he said. “I’ve had to wrestle people to the ground, I’ve had people get chest pains and had to be taken away by ambulance.”

Kiessling said the cases he doesn’t forget are those involving teenagers and children. With those, he says, he has a photographic memory.

“There’s nothing worse than going out at 3 in the morning and telling a mother or father their daughter’s not coming home.”

He also laments cases in which addicted mothers deliver babies that are “addicted to heroin from the first breath.” These babies, Kiessling said, “go through hell.” He described newborns filling neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), fussy, irritable and suffering from seizures. They are often given morphine just to get through their withdrawals.

“There's nothing worse than going out at 3 in the morning and telling a mother or father their daughter's not coming home.” ~ photo by Kelly Powers

A changed profession

When Kiessling started his job nearly two decades ago, he was assisted by only one secretary, who served more offices than his.

“We kept getting busier and busier, and the numbers kept climbing,” he said. He had to plead for additional personnel until eventually he was able to get two full-time deputies in addition to an administrative assistant.

Coroners photograph scenes, collect physical evidence with law enforcement, transport the bodies for autopsies, and finally rule on the cause and manner of death.

Kiessling said there’s one thing lacking in the multitude of drug-related deaths — resolution.

“Makes it difficult to prosecute because it’s much easier if it’s pure fentanyl… Now we can say, well, it’s pure fentanyl, this guy sold him fentanyl, now they’re dead.” Kiessling said. “When it’s mixed drugs, it’s a combination effect. Those are hard cases to get convictions on because of the mix.”

A policy debate surrounds what to call these overdose cases. Across the country, they have been ruled “accidents” or “suicides,” but in 2016, Kiessling stirred up a hornet’s nest when he began ruling many drug-related deaths as homicides.

“I believe, by definition, homicide is the death of an individual at the hand of another,” he said. “My phone blew up for weeks from news media all over the country when I started ruling these cases as homicides. It’s died down now, but we’re still doing it… I think calling these deaths ‘accidents’ is like sweeping the problem under the rug — ‘Oh, just another drug addict.’ ”

Classifying a death as a homicide, however, doesn’t always lead to criminal charges. In Pennsylvania, dealers can be charged with drug delivery resulting in death, though the manner-of-death classification doesn’t automatically mean law enforcement will take a suspected dealer to court.

Kiessling’s office used to base such rulings on a single drug, but in today’s reality, the drugs Gabapentin, fentanyl, heroin, cocaine and more are being sold in a single packet.

“So, if we’re recovering packets at a scene, with a dead body, and no other prescription drugs around, their toxicology reports come back with all these drugs in their system, and we believe they all came from that single packet — that’s a homicide,” Kiessling said. “That person sold that packet, which caused that death.”

The homicide rulings still proving controversial, coroners across the state agree the epidemic has thrown new variables at the job that many never saw coming.

Westmoreland County’s Bacha said the fentanyl is getting “nasty,” requiring his people to use gloves, masks, eye protection and long sleeves – and not wear short pants — to protect themselves against contact with the toxic substance.

“If this stuff gets on you,” he said, “you [run] over to the nearest sink.”

Recently, a member of Bacha’s team opened a container at a scene only to have a white powder blown in his face because of a nearby, open window. Bacha said the man’s heart was sent racing, and he was rushed from the scene to the nearest hospital. The substance turned out to be an antibiotic, likely used for mixing or “cutting” other drugs.

“If that were fentanyl, he would be dead,” Bacha said.

Bacha also said his team has more than pagers strapped to their belts when heading out to a scene. “We carry guns now, because of the whole drug culture… They don’t know who we are, but they think I’m standing between them and their next high. My guys have been swung at, threatened. It’s just crazy.”

A gurney rests against the wall of a Susquehanna Health and Lycoming County Forensic Center hallway. ~ photo by Kelly Powers

The bottom line

“There’s a tremendous cost,” said the coroner association’s Shanaman. “Not only to society, through people dying, but through the cost and the amount of work required to be done by the coroners — in many cases doubling, tripling budgets.”

Shanaman, who writes the annual report related to drug deaths in the state, said autopsies and toxicology tests cost the commonwealth $30 million in 2017. “Just the level of work and number of staff people hasn’t kept up with that,” she said.

In an environment where everyone looks ceaselessly to cut budgets, Dr. Joseph Campbell, the Bucks County coroner, was forced to do the opposite.

“We required a $300,000 budget adjustment earlier this year, for a $1.2 million budget,” said Campbell, the newly elected coroners association president. “It has a lot of budget implications in regards to staffing, overtime, volume, supplies, more autopsies, more pathology services, more toxicology services.” He said the office also had to hire more employees because the current staff was getting exhausted.

Bacha said his office has repeatedly come in over budget.

He said the district attorney he works with in Westmoreland County is “aggressive,” looking often to take on drug delivery resulting in death prosecutions – and that costs money.

“So, we’re autopsying every one of them,” Bacha said. “It cost us almost $500,000 just in 2016 just for the opioids, and that comes out of us, the cost of the autopsy, the toxicology, man hours, secretary hours – add all that together, and it was a couple dollars shy of $3,000. That’s $3,000 per investigation.”

Back in early fall, as Campbell prepared to take over the presidency of the coroners association, which Kiessling held for about two terms, the group met for its annual conference at the Omni Bedford Springs Resort in southcentral Pennsylvania.

Sitting in his dinner blazer, settled in a leather chair, Campbell said the “opioid monster” has struck those who live in both million-dollar homes and rural trailer parks.

“It can seem like it’s almost never-ending,” he said, his voice trailing off slightly. “I mean, I’m hoping we’ll be able to put a dent in the whole process here, but there’s no one answer that anyone can say is going to give us the best result. I think we just keep trying to do everything we can.”

Coping with a crisis

In one week, two of Bacha’s neighbors overdosed. One died, one lived.

“Narcaning your neighbor? That’s not normal. His wife stood there and watched. No reaction,” the father of two said. “You get pretty much exhausted by it.”

Statewide there has been a sizable push for using Narcan, the overdose-reversal drug. In 2018, Governor Tom Wolf announced a two-year project to fund $5 million in Narcan or Naloxone kits in Pennsylvania. However, for years, opioid deaths have piled higher and higher for coroners around the state — the sheer repetition straining staffs and the budgets they work with.

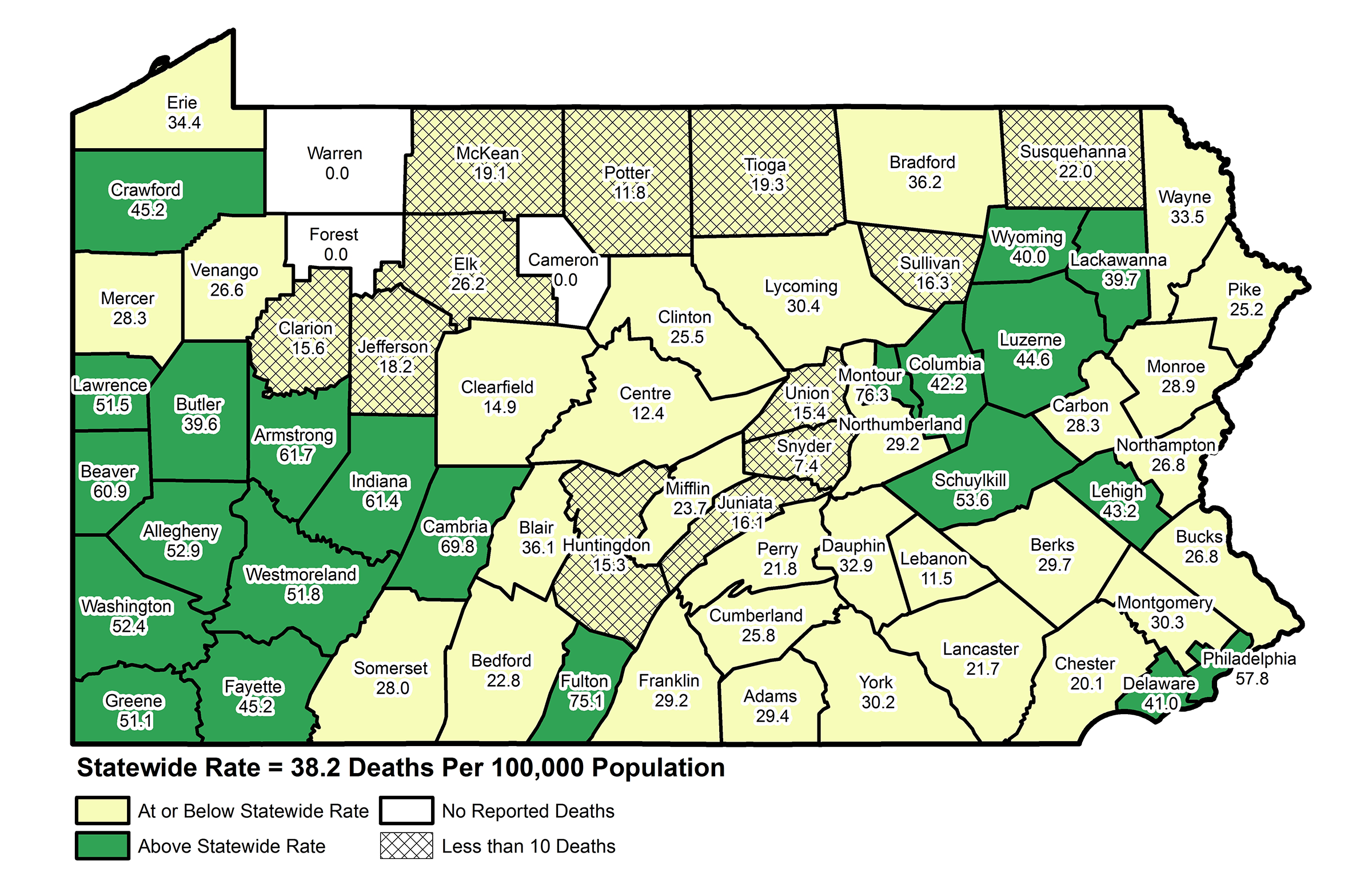

Enlarge

Drug-related death rates by county ~ Pennsylvania State Coroners Association

“Christmas Day two years ago, we had five overdoses,” Bacha said.

So how does a coroner cope?

“I just do,” Kiessling said. “Need to be able to go out, [do] the jobs that we do, put the documents together that we need to, deal with the families. And then we kind of, like a chalkboard, wipe it off and move on. Otherwise, I don’t think you could do this job.”

He said the opioid fight can feel like chipping away at a mountain with a spoon.

“There’s no one fix to this problem,” Kiessling said. “I think there needs to be better treatment resources available in our communities. Many of the counties just didn’t have the drug and alcohol treatment resources to handle this huge influx.”

About a year after her son’s heroin overdose, Miele conducted the first fundraiser for her nonprofit advocacy group called “Saving Lives for Zachary.”

The group had first created a video for a local middle school. Then, she and her children designed a logo and started to organize monthly events, nearly always live-streamed as well. Their goal is to “decrease the stigma, provide education and raise awareness.”

Miele has brought speakers from across the map, recruiting Kiessling as well as drug experts. They discuss topics such as drug effects on pregnancy and children, alternative pain-management methods, and places where recovering addicts can get help. She’s on track to bring former NFL player Randy Grimes, a recovering addict and a public advocate, to Pennsylvania in February.

Are these programs helping?

Bacha acknowledged that drug deaths had climbed in recent years: “We had 22 in 2002, then we went up to 193 in 2017, our highest.” But, he pointed out, as of Sept. 1, his office would be on pace to finish 2018 with about 124 drug-related deaths. That would be the lowest since 2014.

“That’s a significant drop,” Bacha said. He credited increased awareness in the media — TV reporting on drug statistics, TV commercials, billboards — and “police really aggressively making arrests.”

Kiessling echoed the sentiment, adding that his numbers for the year were also coming in slightly lower, as of mid-October. He cautiously credited “warm hand-offs” in local hospitals, in which overdose survivors are connected with recovery-center staff members right in hospital rooms.

Though the 2017 report from the coroners association has yet to be published, Shanaman released a drug-death total of 5,658 for the state of Pennsylvania — a 16 percent increase from the preceding year.

“I’m not holding my breath,” Kiessling said.

11/26/2018