Education Far from War

By Anjelica Rubin

Paper snowflakes taped to the circular glass windows on the exterior of an otherwise drab building in the center of Tallinn are the only hints of what lies within.

Inside, laughter and the occasional shout echo up the winding staircase as teachers usher stragglers into their classrooms and remnants of Estonian independence day celebrations, held the previous week, drape across the ceiling in blue and white flags.

On a whiteboard at the end of one hallway are the words “stop war.” It’s more than a slogan for the 573 students at this school who are also war refugees. It’s a hope, a dream and a prayer for their Ukrainian homeland.

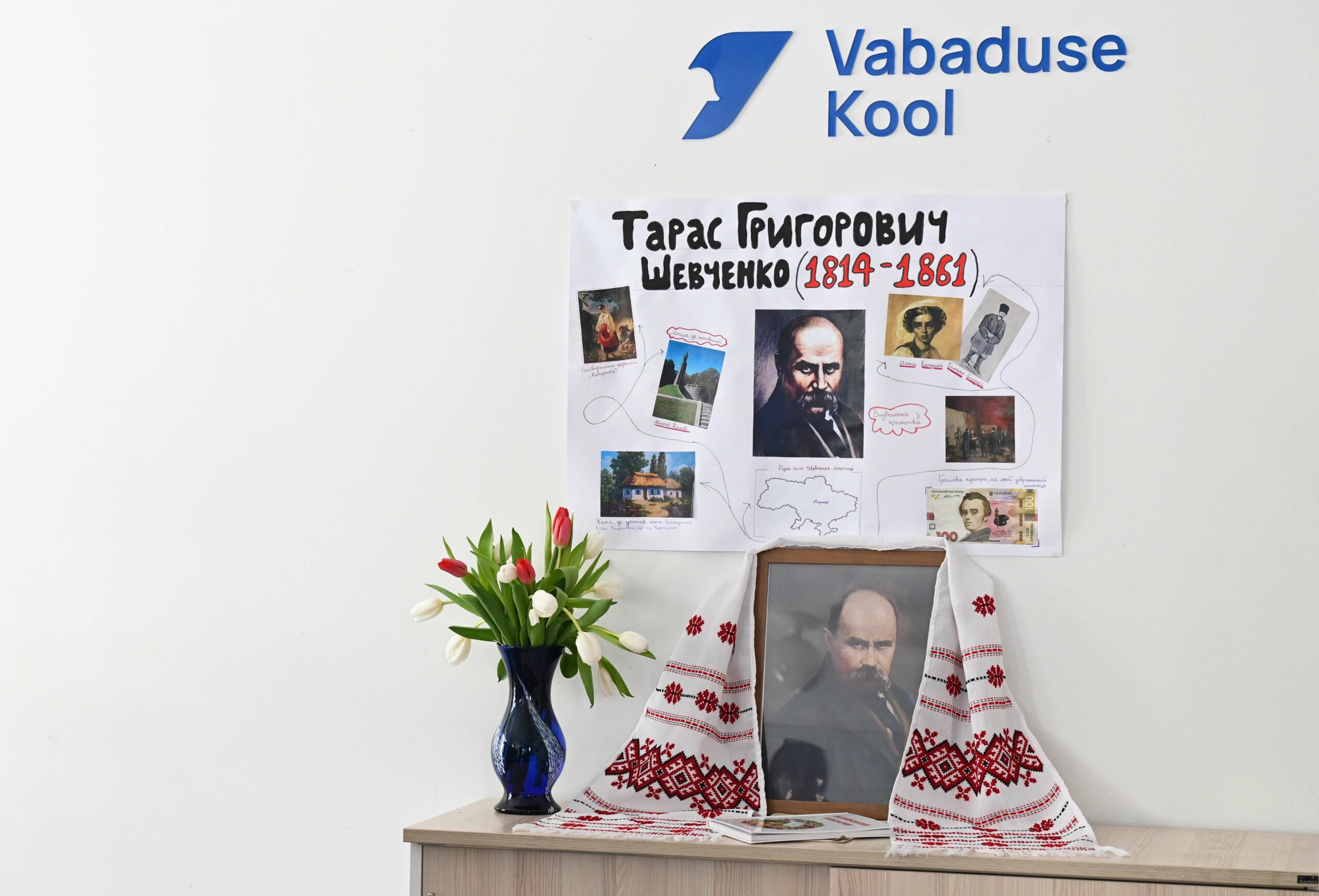

This is Vabaduse Kool — the Freedom School.

Polina Hurets never imagined she’d end up in a school 760 miles from home.

“When we left Ukraine, it was my mom’s decision because it was too dangerous to stay there ,” Hurets, who’s from Hlukhiv, a small town in northeastern Ukraine, said. “I got very upset [by] this because it was my home and I felt comfortable there, but when we came to Estonia, I began to feel more welcomed and calm.”

If Hurets now feels comfortable, it’s partly due to this unique school created by the Estonian government exclusively for the children of Ukraine.

Estonia’s generosity toward its eastern European neighbor is built on a shared foundation of painful memories of Russian and Soviet occupation in the 20th century and as an expression of support and solidarity for Ukraine.

“I think because of the historical background of Estonia, we felt this collective need to help in any way we could because of our close relationship with Russia and the Russian Empire in all its forms, never pleasant,” Liisa Taul, an Estonian language teacher at Freedom School, said. “It has always been brutal throughout the centuries, and the memory of occupation lives on.”

The idea for the school originated in the spring of 2022, just months after Vladmir Putin’s army invaded Ukraine. Estonia welcomed many refugees — ultimately more than 60,000 — more per capita than any other country in the European Union, and the need to place children in academic institutions came into question as the influx of children threatened to overrun the school system, especially in Tallinn.

State-funded, the Freedom School was conceived as a way to prevent disruptions in the refugees’ educations while also teaching them the language of their adopted country.

“Providing Estonian-language education to children is both a constitutional task of the state and a clear political decision today,” Margit Voog, a communications expert for the Ministry of Education and Research, said. “The official state language of Estonia is Estonian therefore, education is conducted in Estonian language based on the Estonian national curriculum.”

Voog said the immediate urgency to have Ukrainian students learn Estonian is not just a legal mandate, but also due to the uncertainty of war.

“We do not know how long the war in Ukraine will last and if and when it will be possible for the refugees to return to their homeland,” Voog said. “Therefore, it is important that they learn the local language as soon as possible, which is best done in an Estonian-speaking school environment.”

But starting a language-immersion school from scratch with no blueprint to follow, was a challenge for the educators charged with launching Freedom School in the fall of 2022.

Olga Selishcheva, the school’s headmaster, was initially skeptical that they could move so quickly.

“First my reaction was like, ‘Are you kidding?’ To make a school for 500-600 students, and we have [only] the summer — it’s impossible. It’s unreal,” Selishcheva said.

Yet the school opened on time in September, following three months of renovations on the Soviet-era building and an intensive period of recruiting, interviewing; and hiring of teachers, staff, and administrators who collectively brought fluency in three different languages.

As a language-immersion institution — offering 60% of its education in Estonian to fast-track Ukrainian children into Estonian society and 40% of instruction in Ukrainian — enabling students to keep up with their studies in their native tongue, the school is one-of-a-kind, even offering English instruction as well.

However, Russian is commonly spoken to bridge the language gap within some classes and hallway conversation. It’s the lingua franca shared by students from countries once occupied by the Soviet Union like Ukraine and Estonia.

Being able to speak in Russian was one reason Danylo Baiduhanov said he feels so comfortable in the country. Baiduhanov, from Kherson, a city in southern Ukraine, enrolled in the Freedom School in October, after he and his mother fled the occupation of his city by Russian troops.

“Honestly, I do like [Tallinn] because it was part of the Soviet Union so a lot of people know Russian and we can communicate,” Baiduhanov said.

Taul said bridging the communication gap with Russian early on in the school year was useful in helping students get acclimated to Freedom School easier.

“They are from all over the Ukraine, collected together here, many against their will because their parents wanted them to leave. It [is] a lot of stress,” Taul said. “It was more important for me to get them to trust me and engage in class, and for that I used Russian.”

Language-immersions schools like Freedom School work best when students start young or have a prior knowledge of the second language.

“Here, we start from zero,” Selishcheva said.

Although Baiduhanov completed his studies in Ukraine, he decided to come to Freedom School to attend university. Estonian higher education is taught exclusively in Estonian — a notoriously difficult language related to Finnish — and as a foreigner without a firm grasp on the language, he wouldn’t be accepted.

“Honestly, it is a very difficult language for me and I think all Ukrainians,” Baiduhanov said. “But our teacher in Estonian is a very kind and good-hearted soul, and it’s easy to learn Estonian with her.”

Vladislav Lushin, the head of communications at the Freedom School, is a native Russian speaker who learned Estonian through the language-immersion model. He anticipated the demand for the language skills students such as Baiduhanov hope to acquire.

“We saw from the very beginning when we started the intake of students that we still have lots and lots of children who want to study specifically here,” Lushin said.

With its large and growing student population, Freedom School is tasked with finding enough teachers with the proper linguistic skill sets at a time when Estonia is facing a national teacher shortage that some see as an educational crisis.

Eneli Kindsiko is a lead researcher at the Foresight Centre, a government think tank that studies trends in education with an eye to mapping a path forward.

She said the teacher shortage has been in the works since long before the war, with the scarcity most noticeable in the STEM fields as teachers sought higher-paying jobs in Estonia’s flourishing IT sector.

But the war exacerbated the problem.

“Understandably when Estonia was hit by an increase of Ukrainian students, it meant that they integrated very well into our schools,” Kindsiko said. “But it increased the workload of teachers.”

The good news — salaries have gone up. “So the teachers get a bit more than average salary,” Kindsiko said — which is close to $2,000 per month.

Taul, one of the school’s faculty members who had no prior experience in education before accepting a job as an Estonian language teacher last year, was living abroad when she first got the teaching itch. After returning to Estonia, she soon heard about the Freedom School.

“I had been thinking about coming back to Tallinn anyway because of the work opportunities here,” Taul, whose primary residence is in Pärnu, said. “Out of sudden emotion, I called them.”

Taul commutes to Tallinn during the week and teaches some of the youngest students at the Freedom School, though she notes she’s been impressed with her students’ maturity and keenness to learn.

“I tear up thinking about it,” Taul said, her eyes watering. “Something about these kids have opened me up more. I feel the love. It’s incredible seeing rosebuds blossom and that’s what I get to see.”

Daniil Shchetinin is another student who came to Freedom School to study in-person rather than online. Arriving with his mother and younger brother from their hometown Zaporizhzhia in southeastern Ukraine, Shchetinin’s first home in Tallinn was aboard the Isabelle, a cruise ship the Estonian government chartered as a temporary home for several thousand refugees from Ukraine.

The ship, which normally travels up and down the Baltic Sea, has been anchored in Tallinn since March due to the overflow of refugees seeking shelter.

“I thought it would be horrible, because well it’s [a] boat,” Shchetinin said. “But it actually [was not that] bad.”

Shchetinin said his family has experienced support from the Estonian people since the beginning and made the transition to more long-term housing and in-person schooling on foreign soil much easier.

“My father is [still] in Ukraine; he is working, he is living alone with our dog,” Shchetinin said. “It is sometimes depressing, but it is our reality. We really hope that he will come here in the summer.”

Daniel Coll is well-attuned to his students’ apprehension. A native of the United Kingdom, Coll taught for two years in Russia. His wife is Russian and so are his children — a background that has helped him at the Freedom School.

He said the curriculum’s language learning targets need to be balanced with the reality these students live.

“This has to be a good experience for them, and if a good experience means saying [for] today’s lessons, we’re gonna just have a laugh [and] talk about stuff then that’s how it has to be.”

Although they rarely have direct conversations about the war in his classroom, Coll said it’s “always there.”

“They often express how they feel about Russia and Russians, which I don’t really comment on as I’ve lived there and my kids are half-Russian,” Coll said. “We don’t as a family agree in any way with what’s happening in Russia [but] it’s hard. My wife is even so ashamed that she wants to change her citizenship.”

The only English-born teacher in the entire school, Coll said he often finds himself taking a few extra minutes translating a meeting or training materials that Estonian and Ukrainian teachers never have to take a second glance at.

But he finds the most reward in building relationships with his students. With the higher grade levels Coll teaches — the equivalent of upper high school levels — it’s easier for him to converse with his students.

And they enjoy conversing back.

“I’m obsessed with English language,” Hurets said, “[since] maybe second grade. I love [Coll’s] class and I enjoy the challenge of it.”

Ultimately, Coll said the Freedom School and his students have been a “breath of fresh air,” which has led to a re-evaluation of his teaching style.

“Do I make a thing of this guy being 10 minutes late every day if he’s coming from 50 kilometers away, or do I just let it go and say, ‘You know, I know what’s going on in your life,’” Coll said. “So I think our standards, my standards, are different at this school.”

Shchetinin said he was surprised by the connection teachers have with their teachers in Estonia. “It’s really different from Ukraine,” Shchetinin said. “In Ukraine, we are not as close, but here in Estonia, in most situations, [the relationship] is more like old friends.”

Kevin Ivanov has been working at the Freedom School for seven months. He is the class teacher for Hurets, Shchetinin and Baiduhanov and is also part of the support team at the school.

“Kevin is amazing. I love him very much,” Hurets said.

Class teachers play a significant role in the development of each student at the school but on the support team, Ivanov’s work varies, anything from helping students with mental health problems to planning out their next steps post-schooling.

Like all teachers at the Freedom School, he’s driven by a sense of mission that goes beyond education. Ivanov said the best part of the job is “being with the children.”

“When I started working it [looked] like everything’s good,” Ivanov said. “But after a few weeks, the students opened up and they started to talk about the life they had before the war. Some of them told me that they don’t feel anything, and they don’t know how to get it back.”

The school has employed psychologists, therapists and educational advisors who can oversee children who may need extra help, according to Lushin.

But the support team contributes to students’ academic success by directly addressing their emotional needs. “They’re doing a very essential job,” Selishcheva said. “Some of [the students] do not even have parents here, so that’s where [the support team] comes in.”

As for the future of a school created out of necessity, Selishcheva said the need will remain even if or when the war ends.

“We have many people [in Estonia] from different countries,” Selishcheva said. “There’s an opportunity there to help integrate them into Estonia too.”

But for the foreseeable future, the school’s capacity is capped. Already, students must apply to get into the school and there is a long wait list.

Recently, however, the number of Ukrainian children entering the school system each day has plateaued. Due to changes in the war situation and living conditions in Ukraine, Voog said some refugees are now leaving Estonia. Some are returning to Ukraine.

Voog does not expect the crush of refugees that poured into Tallinn last year.

“New children and youngsters from Ukraine still enter our school system every day,” Voog said. “But this number has stabilized and is not very high — about 20-40 weekly as of now.”

Hurets wants to go home in the near future and hopes to be educated in person back in Ukraine. “I still feel Ukraine is like my only home and I want to [go] back and I assume it will be as soon as possible,” Hurets said.

But Hurets said she’ll never forget her time in Tallinn—the kindness of the Estonian people, the openness of the Freedom School, the educational opportunities or the friendships she made.

Shchetinin likewise said he’ll always remain grateful for the Freedom School. He plans to stick around after his graduation next year.

“My plans are built around staying here in Tallinn,” Shchetinin said. “I’ll go to university here,” he added, “people are kind to me, they’re always helping.”

“I think for every person at this school, that’s why we so enjoy this work,” Selishcheva said, “why we put in our all.”

In the fall, Selishcheva received an email from the mother of a student at Freedom School. Her child, she explained in her message, hadn’t smiled all summer — they didn’t understand what was going on, they had no friends and they just wanted to go back home to Ukraine.

But because of Freedom School, the mother continued, her child was smiling again and excited to go to school.

Selishcheva said it’s moments like those that make all the hard work and dedication worthwhile.

“When we got this email it was like, ‘Yes, this is why I am here,’” Selishcheva said, “this is my purpose. We can do all we want academically but if our kids are not happy, it [just] doesn’t work.”

~Published on May 2, 2023