The Big House is roaring with excitement, and why not? No. 4 Michigan is leading Big Ten rival Penn State, 35-10, on the way to a 49-10 victory. With 11 minutes left in this 2016 nationally televised game, the Nittany Lions have finally scored a touchdown and are kicking off to the Wolverines.

As Michigan’s Jourdan Lewis fields the ball and surges forward, he is suddenly crushed by a violent tackle.

Joey Julius, right, tackles Michigan's Jourdan Lewis ~ photo by Steve Manuel

“It was the kicker who made the hit!” ABC play-by-play announcer Dave Flemming shouts with excitement and disbelief.

In the world of college football, a kicker typically avoids physical confrontation unless he’s the last defender between the returner and the goal line. No surprise there, since kickers are likely to be among the smallest players on the field.

But Penn State’s kicker – Joey Julius, 5-foot-10 and 271 pounds – does not fit the stereotype.

Julius’ hit on Lewis is so astounding that the network replays it in slow motion, eliciting an “Oh, jeez” and laughter from the broadcast booth.

The Big Ten Network video clip would garner more than 400,000 views on YouTube, approaching the 600,000 views of Julius’ tackle of a Kent State returner in an earlier game. As the redshirt sophomore’s growing social media prominence caught the attention of mainstream sports media, he would be profiled by ESPN.

As it turned out, the Michigan and Kent State games were not the only times Julius found himself getting a lot of social media attention. He recalled recently how he noticed his teammates laughing and joking in the locker room after the shocking 27-10 loss to Temple that opened the Lions’ 2015 schedule.

He thought something seemed off.

When he checked his cell phone, he found 5,000 messages and 10,000 notifications on Twitter. People were taking notice of him, but not in a positive way, even though he had kicked a field goal and an extra point that day.

Joey Julius kicks off against Iowa. Kicking for a Big Ten team wasn't what brought him notoriety. It was his size. ~ photo by Steve Manuel

“I became a viral sensation because of the way I looked,” Julius said.

“People were talking only about my weight and not really about my play. It was hard for me because I want to be known as a kicker. Not an overweight kicker.”

***

Julius, now 22, is no longer a college football player. In the months before the 2016 season when he delivered the resounding tackles on kickoffs against Kent State and Michigan, he was diagnosed with binge eating order at McCallum Place, an eating-disorder treatment center in St. Louis. More recently, Julius has been treated again at the center.

Just as there’s an expectation for what collegiate kickers look like, there’s an expectation that people affected by eating disorders have a certain body type. As Julius notes, “a super skinny girl” is the kind of person the public most commonly associates with an eating disorder.

Again departing from stereotype, Julius is part of a growing population of male athletes with eating and exercise disorders. It’s a population that includes the likes of former international soccer player Paul Gascoigne and fitness guru Richard Simmons.

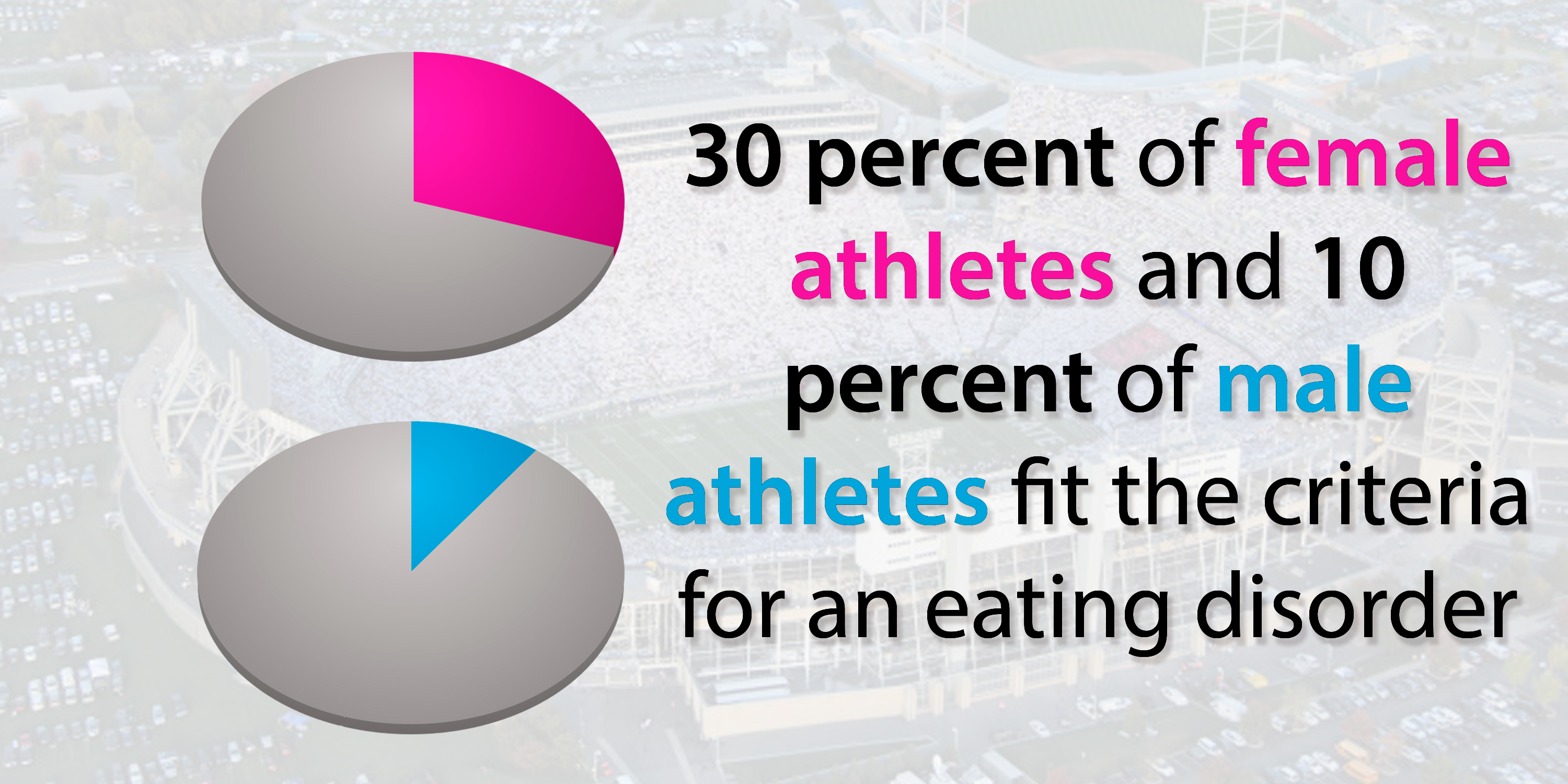

Riley Nickols, a sports psychologist at McCallum Place, said NCAA statistics show that 30 percent of female collegiate athletes and 10 percent of male collegiate athletes meet the criteria for eating disorders.

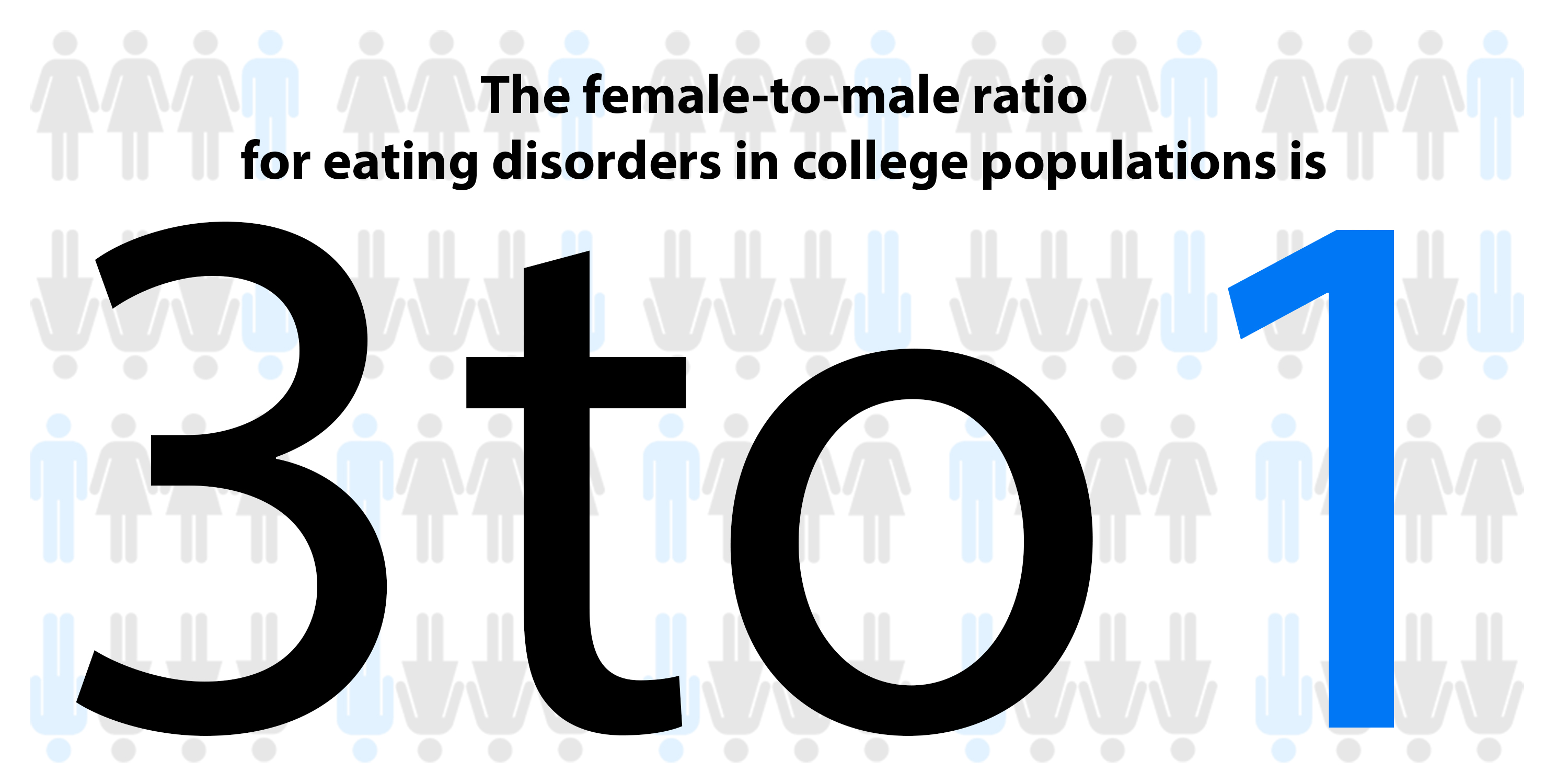

In 2003, according to the International Journal of Eating Disorders, the ratio of females to males with anorexia, an obsession with not gaining weight by refusing to eat, was 10 to 1. Now, the ratio is 3 to 1. The ratio has similarly increased in bulimia nervosa, a disorder characterized by cycles of overeating and self-induced vomiting.

Binge-eating disorder, the most common eating disorder in the United States, differs from bulimia nervosa. By the National Eating Disorder Association’s definition, binge-eating disorder is a “severe, life-threatening and treatable eating disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of eating large quantities of food.” Unlike bulimia, binge-eating disorder doesn’t always result in self-induced vomiting.

Virginia Cox Evans, a NEDA member and clinical social worker who specializes in eating-disorder treatment, said binge eating is fundamentally the same as anorexia. People with binge-eating disorder, she said, “are just feeding their emotions instead of starving their emotions.”

Nickols, of McCallum Place, said binge eating is often viewed as “just eating an exuberant amount of food and not being able to regulate and modulate food intake.”

Often, those suffering from the disorder refrain from eating for long periods of time, he said. “It’s this really vicious cycle of restriction and binge.”

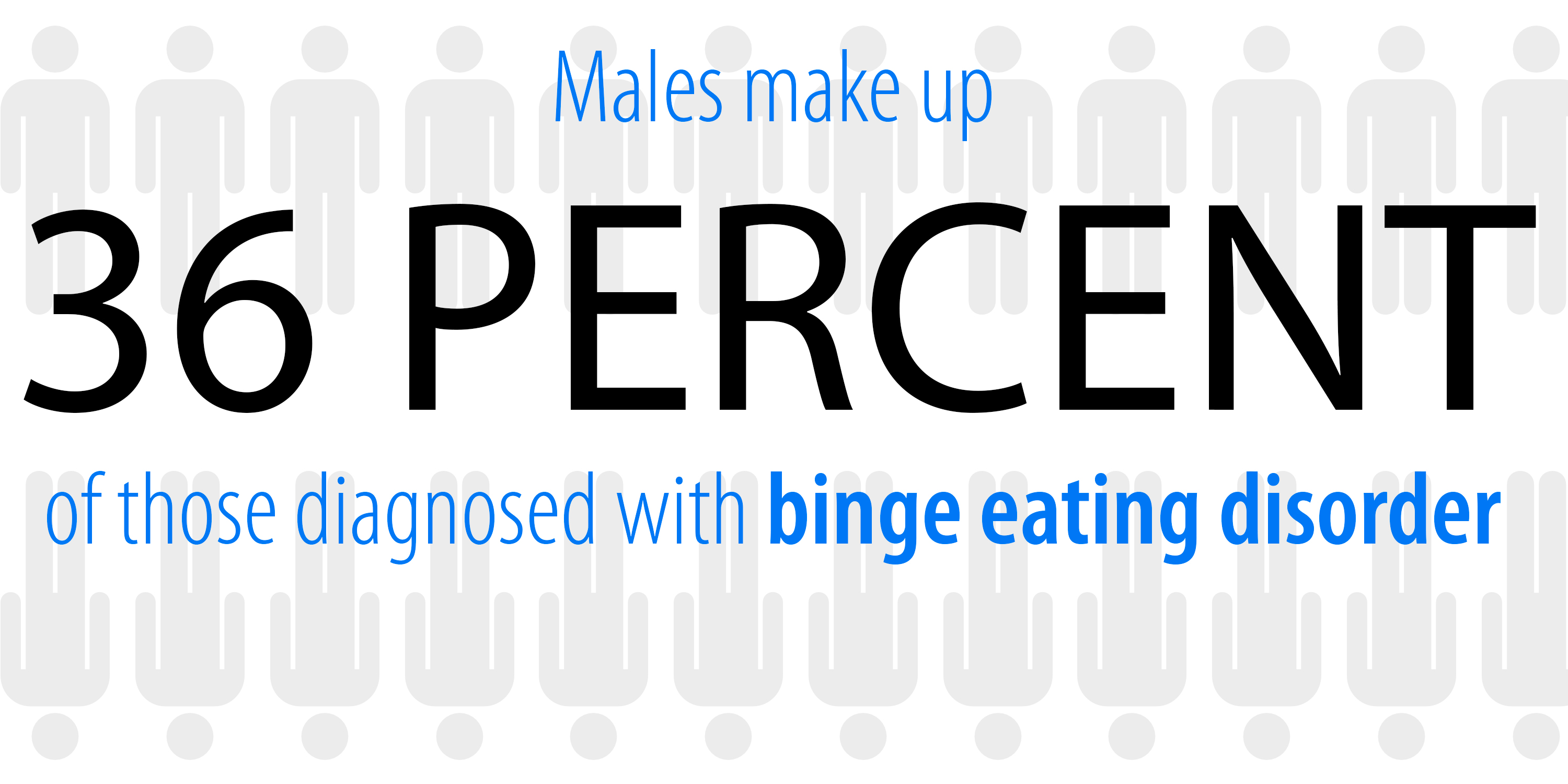

Nickols said men have a 2 percent chance of suffering from binge-eating disorder, making it four times more common than bulimia nervosa. Additionally, males make up 36 percent of the general population affected by binge-eating disorder.

Cox Evans said that two barriers men have to overcome when diagnosing eating disorders are people attributing their disorders to normal growth spurts or the pursuit of six-pack abs.

Nickols says more males are reporting their eating disorders, and he credits this development to recent media attention to men who are struggling.

“I think that is really helpful, and my hope is it kind of destigmatizes the struggle for male athletes,” he said. “It removes some barriers for getting help and care.”

***

Julius has struggled with his eating disorder since he was in grade school . Photo by Mark Pynes

Julius didn’t know what an eating disorder was. It wasn’t covered in his school curriculum.

“I didn’t learn what it was until I went to treatment and they told me I had one,” he said with a laugh.

Julius was admitted to McCallum Place in St. Louis on May 9, 2016, four months before his sophomore football season. He stayed there until late July, and during his treatment he officially received his diagnosis.

But Julius said the erratic behaviors associated with his disorder started much earlier, with instances in his childhood of restricting food intake followed by heavy binging.

Growing up, Julius played soccer. After practice, his father Larry would take him out to eat, even though Julius’s mother had already prepared a meal at home. Eating two dinners a night became the norm, he said.

Julius was struggling with his body image, noting that he wasn’t as “skinny and fast” as his soccer-playing peers. He was picked on constantly, garnering negative attention for his appearance no matter how well he played.

Julius said that when he reached middle school, the disparaging comments started to hurt him more.

That continued in high school. Julius said he got “hooked on diuretics and diet pills and various weight-loss methods that do not work.” Julius began restricting his diet and then sneaking food at night, hiding it where no one else could find it.

The restricting and binging took a new form during Julius’ freshman year at Penn State, where he had unlimited access to dining-hall food.

For Julius, restricting entailed not eating a thing – or eating only small portions – until past 8 p.m. Then, Julius said, he would eat three meals within three to four hours. He would consume 3,000 calories in a single sitting. Often he would be sick afterward.

Cox Evans said eating disorders, including binge-eating disorder, are about control: Those diagnosed are often using it as a mechanism to cope with depression, anxiety and other stressors.

Julius said he had “a lot of mental issues” at the time. “If I had a bad day or something, or if I had a lot of anxiety at that time, binging always sort of helped calm me down. It was definitely a very negative coping skill I would use.”

When he decided to come to Penn State, Julius thought he would be a normal, everyday kicker — or at least as normal as a Division I football player could be.

Originally recruited by former head coach Bill O’Brien, the Hummelstown native made a snap decision to play for the Nittany Lions as a walk-on after speaking with James Franklin, who took over as head coach in 2014.

He thought football would be different from soccer. He thought his weight wouldn’t be as big of a deal.

Soon he found out things weren’t exactly as he thought they were going to be. He was told to do extra workouts to lose weight to become healthier.

“It was hard,” Julius said. “Every time I walked to class, every time I ate in the dining commons, anytime I went out on a Saturday night, I always worried about the way I looked.”

Julius spends at least an hour every day picking out an outfit he thinks will make him look skinnier.

On Oct. 2, 2016, less than a month after his Michigan highlights launched him into the national spotlight, Julius wrote on Facebook about why he had been absent from Penn State football during the spring and summer of 2016.

Joey Julius at his family home in Hummelstown, Pa. ~ photo by Mark Pynes

The Facebook post candidly discussed his journey through diagnosis and admission into treatment, and toward the end Julius encouraged others who were struggling to reach out to him so he could provide information and insight.

In the spring of 2017, Julius was admitted to McCallum a second time.

He said he had told a Penn State athletic trainer that he was contemplating suicide. After a stay in Mount Nittany Medical Center, he returned to St. Louis.

Nickols, the sports psychologist, is the director of McCallum’s Victory Program, the athlete-specific treatment option to which Julius was admitted both times.

Nickols said that at McCallum, all eating disorders, including binge-eating disorder, are treated by regulating eating and using psychotherapy.

Cox Evans said the fact that an eating disorder is a mental illness is occasionally forgotten – and eating disorders aren’t just mental illnesses: They’re the number one killer associated with mental illness, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

“It’s never just solely about the food,” Nickols said. “I think we’ve never seen an individual come into our care with ‘just an eating disorder.’ ”

Nickols said a big part of the treatment was the way dietitians help patients tune into the body’s natural hunger and fullness cues to regulate food intake. Then there is the psychological component, addressing and understanding the emotions that cause bad eating habits.

McCallum sports psychologists and sports dietitians who specialize in eating disorders have developed a treatment system geared for athletes.

McCallum also has a male-specific group integrated into its care, something that he said combats the feelings of isolation one might experience when he has an eating disorder.

“When there are shared experiences with others, especially other men who have similar challenges and struggles, that can be quite healing in and of itself,” Nickols said.

***

Like Julius, Ryan Althaus was an athlete, competing intensely in cross-country and other endurance athletics while attending high school in his native Annapolis, Maryland.

But before that, when he was 7 years old, he made his cancer-ridden father weep in pain. It was an accident – childhood rambunctiousness led him to bump into a chemotherapy pump – but the moment stuck with him.

Althaus, now 34, said the incident made him realize “I would do anything in my power not to hurt anybody.” His response to the guilt he felt was “self-deprivation” and “starving myself.”

He said his eating disorder emerged during his sophomore year of high school, though, like Julius, he didn’t immediately recognize the signs.

In general, he said eating disorders are a “very neglected thing in our school systems.”

“It took me so long to recognize it as an eating disorder because I never knew what an eating disorder was,” Althaus said. “My first introduction to eating disorders was walking through my own one and just figuring out, ‘Wait a minute, this isn’t normal.’ ”

Althaus said he was in love with the feeling of deprivation, the feeling he got after an intense athletic workout. When he recognized he could get that same feeling through self-starving, his eating disorder kicked into gear.

Althaus described the feeling as “absolute release” – a spiritual and emotional purging that helped him get over the guilty feelings he was harboring. At times, he said he looked into the mirror and thought he was too skinny, but that didn’t stop the deprivation.

According to NEDA, males represent 25 percent of those with anorexia nervosa. Additionally, men with anorexia have a higher mortality rate because they are typically diagnosed later than their female counterparts.

Althaus said that if people viewed eating disorders as less “scary,” it would help more people come forward.

“An eating disorder is simply an unhealthy relationship with food in our society,” Althaus said. “I think if our society had a bit more fun with it, had more of a dialogue with it and laughed at our goofiness when it comes to food … I think it could be really healing.”

After his initial diagnosis and treatment, Althaus continued to compete in endurance events but stopped after his fifth Ironman triathlon “broke” him in 2015, he said.

“That’s when all of a sudden I realized, ‘You know, I’m not having fun anymore. And not only am I not having fun anymore, I’m doing damage. I don’t feel good.’ ”

Cox Evans, the eating-disorder treatment expert, said participating in advocacy and starting a conversation can be an important healing process in itself. She also stressed the importance acceptance plays in recovery.

“If you don’t own it, you can’t work on it,” she said.

For Althaus, the former endurance athlete, advocacy has taken the form of Sweaty Sheep, a movement he started in 2010 in Louisville, Kentucky. Originally it was intended to be program that connected physical endurance to spirituality. After moving in 2015 to Santa Cruz, California, he reworked the program to use recreation to “break down faith, social and economic barriers.”

Instead of solely exercise, the mission focuses on a more playful approach to physical activity – for example, going out with friends to swim rather than doing timed laps in a pool.

Another program Althaus has been involved with is runPossible, a fitness-based program that treats addictive disorders ranging from eating to drugs. Althaus said runPossible is all about forming relationships and starting a dialogue.

“It’s really interesting when all of a sudden a meth addict starts sharing with somebody with an eating disorder,” Althaus said. “The meth addict is very self-aware with their addiction and their deceitfulness. The person with the eating disorder is in the closet. They don’t even know they have an eating disorder. So when they start talking to someone with an addiction, it actually reveals their deeper addiction.”

***

For Julius, advocacy has taken a different form – speaking publicly, attending conferences and “trying to spread the word as much as possible.”

Julius is now enrolled at Penn State Harrisburg. He and his doctors chose the Harrisburg campus to see if it would help with his recovery. The university’s branch campus is closer to his hometown, so he has the support of his family.

Julius hopes to use his experiences to help others. ~ photo by Sarah Vasile

“It sucks that you have to do trial and error with your own life,” Julius said, “but it was one of those things where it was like, ‘All right, we tried and we failed this way, let’s try it this way and see if it works.’ ”

With the absence of football in his life, he has found new ways to occupy his time: working, golfing and playing video games.

“I just try to keep my mind busy,” he said.

Although Julius wasn’t entirely sure he was ready to return to State College, decided to attend Penn State’s 2017 home game against Michigan.

A lot had changed since Julius had gone viral on social media the year before. The Nittany Lions were undefeated and ranked second in the country, and they went on to beat the No. 19 Wolverines, 42-13.

Instead of being suited up, Julius was a fan attending the nationally televised “White Out” game at Beaver Stadium.

“I’ve always experienced it as a player,” Julius said. “I have been to three White Outs so far, and that was one of the most fun I’ve ever been to, as a fan.”

Three weeks later, on Nov. 13, Julius returned to Happy Valley again. He was the keynote speaker at a Mental Health and Wellness Week event, which focused on body positivity. Nearly 300 people listened to his story, and he left them with a piece of advice.

“If I try to compare myself to everybody else, I will surely despair,” he said. “I am not like you, and you are not like me. If I keep trying to be like somebody that I’m not, I will not be anything.”

Julius said his biggest dream is to become a therapist and use his experience to help people.

“As simple as it sounds,” he said, “if just one person gets help, I’d be satisfied.”

~ 12/5/2017