A father's uphill climb to defeat his sons' deadly disease

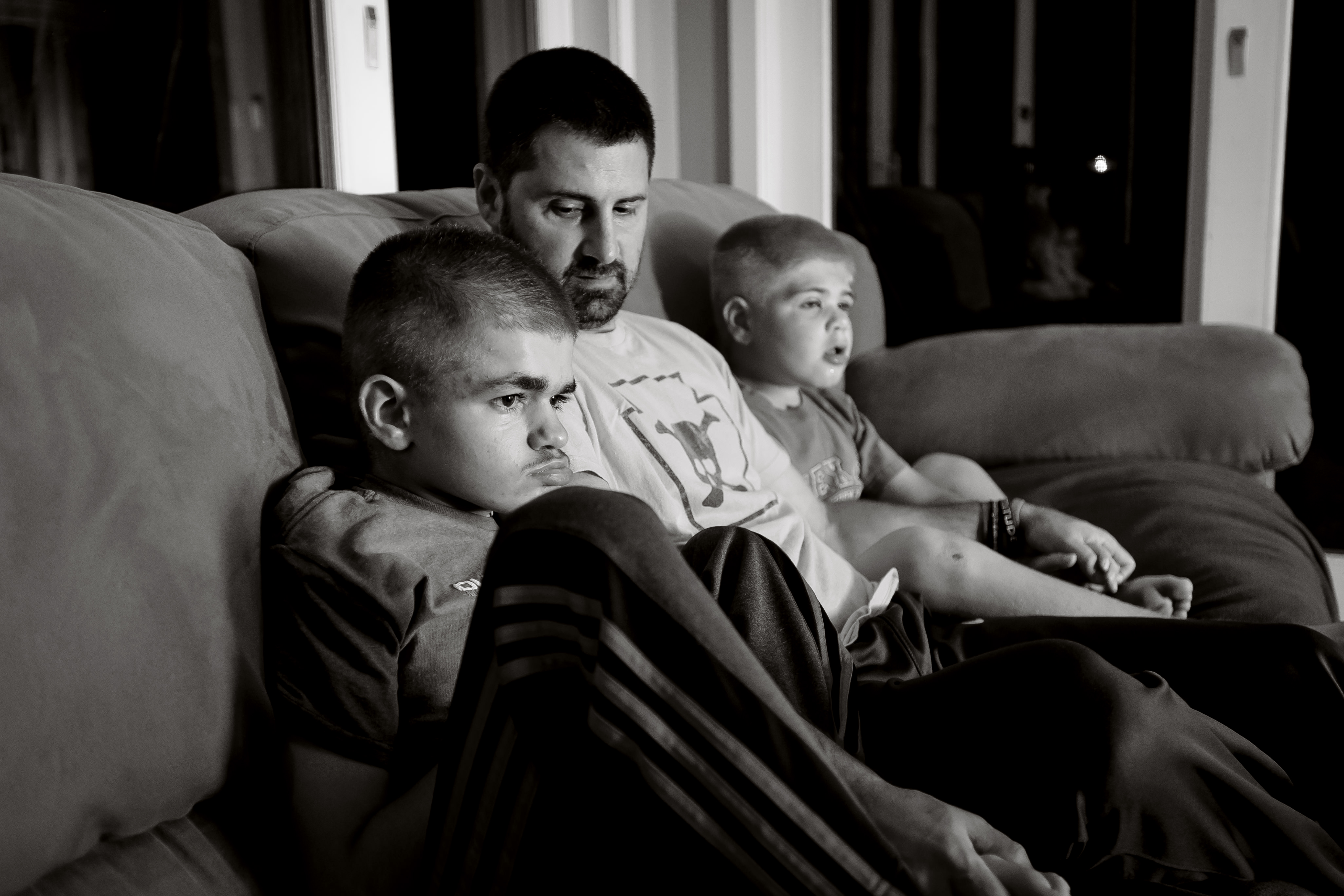

Brayden Kapes, 8, sits in his dad's lap next to his brother Ryan, 11, watching "The Backyardigans," a children's television show, at their home in Wilmington, Delaware. ~ Photo by Dan Salvo

In the summer of 2009, Carl Kapes received the devastating news that his 4-year-old son Ryan had been diagnosed with a rare, deadly and incurable genetic disease named Sanfilippo syndrome.

But the most difficult day of his life, at least to that point, Kapes said, would not occur until two months later.

That’s when Kapes found out that his 2-year-old son Brayden also had Sanfilippo.

Driving home from the doctor’s office that day in September, Kapes felt as if a family member had just died. He reeled from the harsh likelihood that both of his children would die before they reached adulthood. For three days he surrounded himself in his suburban Wilmington home with his closest family members and just cried.

In the seven years since, Kapes has raised a million dollars for a cure and, as part of the fundraising, has literally climbed two of the tallest mountains in the world. Yet, he said in an interview, raising children with a degenerative disease led to heartbreak that “no parent should ever have to go through.” That heartbreak stressed and ultimately broke up his marriage.

Sanfilippo is inherited through a genetic defect carried by both parents. A child with the disease experiences debilitating neurological problems and mental disabilities that resemble a severe case of multiple sclerosis and autism. The child’s physical development plateaus, usually before the age of 10, followed by gradual degeneration and eventual loss of physical abilities such as talking, walking and controlling limbs.

As the physical condition of a Sanfilippo patient regresses, the child enters a vegetative state and typically dies before age 20.

“I can’t even explain how awful it is to hear that your child is going to die from a disease with no treatment or cure,” Kapes said. “It just changes everything you live for or strive for.”

Carl Kapes feeds Ryan because Ryan no longer has the muscle control to feed himself. ~ Photo by Dan Salvo

***

After receiving Ryan’s diagnosis Kapes and his wife, Jennifer, were told by the family’s geneticist, Dr. Karen Gripp, that their 2-year-old son Brayden, who had no symptoms, would also need to be tested for the disease. As they anxiously awaited the results, they convinced themselves that Brayden was going to test negative.

“We went to the beach, and when we got back we were supposed to go into the doctor’s office that Wednesday,” Jennifer Kapes said. “But I called on Monday and told them we couldn’t wait anymore. And they said to come in.”

Carl Kapes said that when the doctor asked the couple to come in and review the results, they both realized the test result was positive.

“These are the things you look back on and remember.” Carl Kapes

“These are the things you look back on and remember,” Carl Kapes said. “If Brayden didn’t have it, they would have told us he’s fine. No need to come in.”

The visit to the office confirmed their worst fears.

***

Sanfilippo syndrome was named after Sylvester Sanfilippo, who conducted a comprehensive study of the disease at the University of Minnesota in the early 1960s.

The disease is also known as mucopolysaccharidosis III, or MPSIII. According to the National MPS Society, it affects 1 in 70,000 children. In comparison, multiple sclerosis affects 90 in 100,000 adults, according to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and autism affects 1 in 68 children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sanfilippo is an autosomal recessive genetic disease, which requires both parents to be unaffected carriers of the abnormal gene in order to conceive a child who could be born with the disease. The child has a 1 in 4 chance to be born affected and a 2 in 4 chance to be born an unaffected carrier.

Mucopolysaccharides are long chains of sugar molecules that aid in the construction of connective tissue. During the continuous building process, the body breaks down the used mucopolysaccharides, most of which are then absorbed and recycled. A child with Sanfilippo is missing a key enzyme that allows the breakdown. Sanfilippo has four classifications, A, B, C and D, which are determined by the particular enzyme that is missing. Without the enzyme, mucopolysaccharides remain stored in the body’s cells, which causes eventual loss of speech and hearing, and the ability to walk and eat. A child in advanced stages of the disease suffer from seizures that can result in death.

The average lifespan of a child with the disease is between 15 and 20. Although the long-term prognosis is bleak, the first two years or so of a child’s life with Sanfilippo often are normal, which makes the disease difficult to detect early on.

***

Brayden watches "The Backyardigans" ~ Photo by Leon Valsechi

Ryan was born Nov. 28, 2004, and showed no signs of abnormality. He was a happy baby and developed into a social toddler who loved to be around other children. Like his father, he had a passion for baseball and basketball. When he wasn’t watching his favorite television show, “The Backyardigans,” a children’s cartoon, he was dancing around the house and spreading joy with his infectious smile.

Ryan’s first symptoms came when his speech started to lag behind other children in his daycare class and he was struggling to become toilet-trained. Ryan was checked by the family’s pediatrician, but the symptoms were not uncommon among toddlers and there was no suspicion of anything deeper.

When Ryan neared 2 years of age, he began to exhibit symptoms of hyperactivity, which is also a common behavior in children with the disease. As the disease progressed and the symptoms recurred, Carl Kapes began to think that there was something more complex at work.

Carl Kapes lifts Ryan's legs one step at a time as they climb the stairs for a bath. ~ Photo by Dan Salvo

On a recent September afternoon, Ryan draped his right arm over his father and leaned all of his weight on him. Slowly they climbed the stairs of the home. Ryan tried to lift his leg to take the next stair, but he had no success until his father grabbed his ankles and lifted his legs. After almost two minutes they reached the top of the stairs. Kapes removed Ryan’s soiled diaper and lifted him into the tub, where the warm water calmed him.

As he stood in the bathroom watching Ryan, now 11, Kapes reflected back on the early symptoms:

“At that point we had gone far enough to know that something was wrong,” Kapes said. “The doctors went through a list of things like autism, but they found no smoking gun, which is when they decided to send us to our geneticist.”

One of the first tests geneticists run is a urinalysis. Sanfilippo is a storage disease, which means the mucopolysaccharides that fail to be broken down are stored in the body and eventually make their way into the child’s urine.

The urine test showed a high concentration of mucopolysaccharides. Dr. Gripp then ordered a blood test to screen for Sanfilippo. The results confirmed that Ryan had the disease.

“Getting Ryan’s diagnosis was terrible in its own right,” Kapes said. “A few weeks after Brayden’s diagnosis, I came to terms with it and I decided I have to enjoy my kids while I have them. But at the same time I was going to do whatever I could to find a treatment or cure for the disease.”

***

With a new focus based on the boys’ diagnoses, Kapes discovered the National MPS Foundation, formed in 1974 to support families who have children with MPS diseases. The foundation has been instrumental in raising awareness and money, but Sanfilippo is one of 13 classifications of MPS and Kapes was hoping for a Sanfilippo-specific group. That led him to the newly formed Team Sanfilippo Foundation (TSF).

At the end of 2009 Kapes met with TSF parents whose children suffer with the disease. TSF, much like the MPS Foundation, was formed to raise awareness about the disease and act as a support system for families, but the larger goal of the foundation is to raise money for Sanfilippo research.

Patty Taormino of Baltimore, vice president and co-founder of TSF, recalled the energy Kapes brought to the foundation.

“Carl was a fighter from moment one,” Taormino said. “Like most parents who find out their child has the disease, he asked a ton of questions and was eager to try and find a cure, but he was different and we were excited to have him.”

Taormino’s son, Jesse, was diagnosed with Sanfilippo in 2001 when he was 6 years old. Earlier this year, at the age of 21, he graduated from the Maryland School for the Blind, a special-needs high school near the family’s home. Taormino credits Jesse’s ability to exceed the life expectancy of a child with Sanfilippo to her 15-year dedication to natural therapies and dietary supplements.

Despite what she perceives as the success of the supplements, Taormino said her focus is to keep Jesse “comfortable” in the latter stages of the disease.

The Kapes boys are getting Taormino’s customized regimen. Standing at the counter in his kitchen, Kapes adds a combination of dietary supplements and medications into a bowl of yogurt. Like a scientist in a lab he weighs powders, breaks open pill capsules and stirs vigorously until the “cocktail,” as he calls it, is ready. The regimen is administered twice daily.

As he spoon-feeds Ryan, who can no longer control his hands well enough to feed himself, Kapes explained that Taormino’s approach to treating Sanfilippo is legendary in the community.

“I like to call her the Sanfilippo whisperer,” Kapes said.

Over 50 families come to Taormino for advice about dietary supplements. While there has been no medical research on the supplement’s effects on Sanfilippo, all the families she advises are seeing positive results, such as regular bowel movements, decrease in muscle and joint pain, and a reduction in the number of seizures.

“At first I was grabbing at straws and looking for things that would work on the kids,” Taormino said. “Then I started to research diseases that had similar symptoms to Sanfilippo, and I found out that those therapies and supplements cross over very well.”

Much like children with autism, Sanfilippo children often suffer from acute cases of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Taormino reached out to doctors who treat autism and found that a combination of zinc and omega-3 could increase attention spans. She started Jesse on the regimen and within a few days he showed improvement. That caused her to dig deeper into dietary supplement research.

Sanfilippo children struggling with ADHD are restless, and if they still have their mobility, they often walk along the same paths inside their homes. Kapes has two rooms in his home that he has baby-proofed to allow Brayden to move about freely. Kapes, who is remarried, and his former wife, Jennifer, share custody and care of the boys.

Ryan, who can only walk with assistance, sits on the couch tightly squeezing Boomer the family dog’s Cincinnati Reds ball. Brayden paces between the two rooms. “The Backyardigans” are on both televisions, and the cartoon keeps Brayden’s attention for three to five minutes before he walks from room to room with a curious look on his face. Although his attention span is short, Kapes said it has stayed steady, which he credits to Taormino’s advice.

The boys watch "The Backyardigans" with their dad and Boomer the family dog. ~ Photo by Dan Salvo

“Anything that gives the kids one extra minute of attention span can be important, not only for them, but for you as well,” Taormino said. “Having a child with the disease can be extremely difficult at times and that extra minute can help to maintain your patience.”

Kapes said he believes Taormino’s supplements are slowing the boys’ regression. He and Taormino have developed a friendship that has strengthened TSF as a support group for families with Sanfilippo.

The friendship began near the end of 2009 when Kapes held his first fun-run to raise money, and Taormino attended. Shortly after the run, he began holding charity golf tournaments in Wilmington and Sugarloaf, Pennsylvania, just a few miles from his hometown of Weston, near the Pocono Mountains. The golf tournaments, which start at 11:28 a.m. to honor Ryan’s birthday, usually raise about $30,000. Each tournament draws about 100 players. Kapes was happy with the success, but he knew that if any major research was going to be done, the fundraising needed to increase dramatically. And it did.

***

In early 2011 Kapes and TSF discovered the Pepsi Refresh Project, a series of month-long contests that allowed the public to vote for a specific cause through Facebook, the Pepsi Refresh website and text messaging. Each month’s winning cause would receive $250,000.

For a month, Kapes flooded social media with vote requests and pleas for a “share” or a “like.” He called everyone he thought might care, spoke into any ear that was tilted his way, and at the end of the month he received joyous news: TSF had won the $250,000 prize for January.

“We don’t have many victories with this disease,” Kapes said, “and that was a big one. But I knew it was just the start.”

The money Kapes has raised for TSF was donated to gene therapy research being conducted at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, in Columbus, Ohio, by two Ph.D.s, Haiyan Fu and Douglas McCarty, and a medical doctor, Kevin Flanigan. The gene therapy is attached to a virus that has the ability to cross the blood brain barrier, which allows access to the central nervous system. At the time Fu’s research was unique in the battle against Sanfilippo, which motivated Kapes and TSF to search for more ways to raise money.

After the Pepsi refresh victory, Kapes and his family were invited to Give Kids the World Village in Orlando, Florida. The village is a nonprofit resort that provides free, weeklong vacations for the families of children diagnosed with life-threatening illnesses. The package includes theme park tickets, food and transportation.

On the trip Kapes met a family with a relative who had climbed Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa to celebrate a family member who had defeated cancer. Kapes decided he would climb Mount Kilimanjaro (“a no-brainer”), but he wanted to do more. “I needed a way to get the word out and somehow find a way to raise money,” he said.

***

“I was immediately impressed by his tenacity and graciousness.” Nick Mcllwain

During his morning commute to his job as an electrical engineering manager at Delmarva Power in Wilmington, Kapes often tuned into the “Preston and Steve” radio show broadcast by WMMR in Philadelphia. He decided to reach out to the producer of the show, Nick Mcllwain, to ask him to spread the word about the disease and the climb he would be making.

Kapes emailed Mcllwain and received a gentle no. Undeterred, Kapes persisted and finally had Mcllwain’s ear.

“I was immediately impressed by his tenacity and graciousness,”Mcllwain said. “He wasn’t overbearing, and the open and honest way he spoke about the disease intrigued me.”

McIlwain was on board.

In early 2012, Kapes, a former college baseball player, and McIlwain, who had not been an athlete, began working with personal trainers. WMMR listeners began pledging their money on line and by calling in.

In August, ready to go, Kapes and Mcllwain landed in Africa prepared to climb the largest mountain on the continent at just over 19,000 feet.

As they were making the five-day climb, Kapes said the guides who spoke in Swahili were constantly saying “pole, pole, pole,” pronounced polay, which means slowly. The climb demanded stamina and patience, qualities that Kapes said being a parent of a child with Sanfilippo prepared him for.

“There are a lot of parallels you can draw when comparing climbing a mountain to experiencing Sanfilippo,” Kapes said. “It’s clearly an uphill battle, and there are times when I feel like I might not make it, but there’s also plenty to be hopeful for.”

Much of the hope Kapes speaks of comes from the money raised to fight the disease. The Kilimanjaro climb raised nearly $100,000. That went directly to Fu’s gene therapy research.

***

The highs Kapes experienced in Africa clashed with a dose of reality when he returned home. The boys were physically regressing. and their cognitive functions were deteriorating.

One way that Kapes measured Ryan’s regression was by encouraging him to sing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” At one point Ryan was able to sing the song in its entirety, but as his conditioned worsened, he struggled to make it halfway through the song. Eventually he could not sing a single note.

Kapes’ marriage was also struggling. That kind of stress is not uncommon for parents whose children suffer from genetic diseases. According to a study published in November 2015 by researchers at the University of Wisconsin, 22 percent of parents who have children with developmental disabilities experience divorce.

“We had a different approach to dealing with the disease,” Jennifer Kapes said. “He was much more focused on finding a cure and wasn’t going to take no for an answer. But as a mom, I just wanted to take care of them.”

Kapes added that he and Jennifer shared less time alone with each other as the disease progressed. That led the couple to grow apart. They divorced in 2012. They now share custody of the boys and live within five miles of each other.

As the marriage was becoming more complicated, Kapes was in the midst of his most productive stretch of fundraising. After the success with Pepsi Refresh, Kapes discovered a similar online contest run by the Vivint Home Security Company. Supporters of competing causes vote on social media to determine the winner.

TSF was one of five regional winners awarded $100,000. With the Vivint award, Kapes had helped raise nearly $500,000 for TSF in less than a year. The money advanced the research to a point where a therapy was becoming a reality, but the research doctors needed a bridge between the lab and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to get Sanfilippo children the help they desperately needed.

***

In early 2013 Abeona Therapeutics was formed by Tim Miller, a Ph.D. who had spent over 13 years researching gene therapy and regenerative medicine. Miller formed Abeona in conjunction with Nationwide Children’s Hospital to focus Sanfilippo research on developing therapies and finding a cure. Abeona reached out to advocacy foundations around the world to connect them with the research being conducted at the hospital.

Among the foundations that joined in the fight were TSF and Ben’s Dream from the United States, Foundation Sanfilippo from Switzerland, Stop Sanfilippo from Spain, and the Sanfilippo Children’s Research Foundation from Canada. The money raised by the foundations helped to push the gene therapy into clinical trials.

Fu, McCarty and Flanigan have developed ABO-102, a viral-based gene therapy administered through a one-time injection into the central nervous system. The brain is protected by a blood-brain barrier, which acts as a filtering mechanism to protect against viruses and other potential neurotoxins. ABO-102 is attached to an innocuous virus that has the ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier. The therapy delivers a normal copy of the defective gene. That allows organs to produce the missing enzyme in Sanfilippo patients. The therapy helps to repair cells damaged by the disease and can prevent further damage. Children who receive the therapy will not see a complete reversal of degeneration caused by the disease, but if the drug is successful, they should not experience further damage and can expect a longer lifespan.

'I thought this is it, my boys have a chance.” Carl Kapes

After more than 18 years of research, the Food and Drug Administration approved the therapy in February of this year. At the end of May, Abeona Therapeutics issued a press release confirming that ABO-102 had been administered to a child with Sanfilippo A.

Ryan and Brayden both suffer from Sanfilippo A, which made them candidates for the therapy. Kapes was overjoyed by the announcement.

“We were so confident in what Tim and Dr. Fu were doing and I really felt like it was going to work,” Kapes said. “Then the announcement came and I thought this is it, my boys have a chance.”

***

Children who are candidates for the therapy need to be tested for the virus that carries the therapy through the blood-brain barrier. If children test positive for the virus, it means they carry the antibody that destroys the virus – and can’t be candidates for the therapy.

Once again, Kapes was waiting for an important test result.

And once again, his hopes were dashed. “Ryan tested positive for the virus and that eliminates him from the trials,” Kapes said. “That was the lowest point of my life. You ride that roller-coaster of ‘OK, there’s no treatment,’ and then you fight for years, you get something together and think, ‘My kid has a chance,’ and then you get the news that your child can’t be treated. I was just like, ‘Are you kidding me?’ ”

Brayden did not test positive for the virus, which made him a potential candidate, but there is uncertainty about which children will be chosen. As he waited for the decision on Brayden’s participation in the therapy trials, Kapes quickly shifted his focus to raising more money for research that could find a way to get Ryan treated as well.

“You just gotta pick yourself up and move on,” Kapes said. “The thought of being depressed and sad wasn’t in the cards for me.”

That was his lowest point, and the only way was up for Kapes. He chose Mount Rainier in Washington state for his next challenge. He went into training again. With almost seven years of struggling each day to manage the boys’ disease, he thought he was better prepared for this climb. “It was the most physically and emotionally exhausting thing I’ve ever done,” Kapes said. “Kilimanjaro was basically a long and challenging walk, but Rainier was steeper and we had to navigate rocky cliffs, snow-covered glaciers. And there was a real danger that you could fall into a crevasse.”

Kapes was joined on the 14,000-foot climb by Miller, the researcher; Mcllwain, the Philadelphia radio executive; and Lauren Harris, Mcllwain’s former co-worker. Over four days in August the group ascended the mountain and experienced a changing landscape. Lush green trees and colorful ground cover disappeared; in their place were gray jagged rocks and sheets of glacier ice.

At nearly 12,000 feet Mcllwain and Harris were unable to continue. Fatigued, sore and blistered, Kapes and Miller pressed on. Nearly four days after the journey began, the two shared an embrace in below-zero weather as the wind whipped across their faces.

“In that moment all of my life flashed before my eyes with a rush of emotion and all of the physical pain just went away,” Kapes said. “My feet were blistered and my legs were hurting, but it was all worth it.”

Kapes said he was reflective as he descended the mountain. He said he felt incredible pride for what he had accomplished, but as he looked back on all of his fundraising efforts, he wasn’t sure how much more he could do. He realized he also had two big reasons to slow down.

Kapes and his second wife, Ashley, married in 2014 and welcomed a son, Bryce, earlier this year. The two met when Kapes was training for the Kilimanjaro climb.

As they planned their future together, the couple decided Ashley should be tested for the Sanfilippo gene. She tested negative, and the two embarked on their own journey.

“I feel like it’s time to pass the torch to the families who are beginning their journey with the disease,” Kapes said. “I think we’ve put our stamp on this thing, and it’s gratifying. But I truly think that 10 years from now there will be a cure because of the fundraising by all of the Sanfilippo foundations.”

Carl and Jennifer Kapes' marriage ended in 2012 from the stress of the disease. ~ Photo by Dan Salvo

***

The future is unclear for Ryan and Brayden. Brayden is losing control of his hands, and it makes eating a messy process.

Kapes stands at his dinner table feeding Brayden with a spoon while Ryan restlessly rocks in the chair across the table. “The Backyardigans” plays on a laptop as the boys watch. Brayden occasionally reacts to the show with a gleeful screech, and Ryan moans with a monotone rasp in his voice.

Kapes shares his thoughts on their future. “To be honest, I’m not sure Ryan is going to benefit from the treatment, and my biggest fear is he will die from a seizure in his sleep,” he said. “But I think Brayden has a chance.”

On Oct. 14, Kapes’ resolve was tested once again. Kevin Flanigan, the medical doctor on the research team, phoned to tell him that Brayden would not be included in the next set of clinical trials.

“I’m not sure I can pull myself up off the mat yet again,” Kapes said.

Flanigan explained that Nationwide would accept three children for the next round of trials who have not yet reached their developmental plateau. The therapy drug is expected to have the best results in children who are still gaining skills. Positive results, which the first trials showed, could mean that the drug will hit the open market quicker. Brayden plateaued over a year ago, and with the disease now eroding his abilities, he is going to be left behind for now.

“Time is running out,” Kapes said. “I really thought if anyone was going to get their kid into the trials, it would be me. We’ve come all this way, and I spent seven years raising all of this money. It just felt like a slap in the face.”

The sadness in his voice was evident, and his usual upbeat tone was replaced with a mixture of anger and defeat.

But the father who climbed mountains to cure his boys would not stay down for long. A few days later, there was pep in his voice again. “I did all of this for my kids,” Kapes said, “but at the end of the day, I want to make sure that no parent has to deal with this.”

Carl tucks the boys into bed. ~ Photo by Dan Salvo

~ published 10.27.2016 ~

Carl you still amazing and yes this tragedy of Sanfilippo sucks! If not for the pioneers before us and then our own generation of foundations with the hard work that has been done, and now the easier and successful ability of Social Media, the newer foundations would still be at square 1! They would have nothing still. It’s sad that our kids will never see a cure after such efforts. (maybe Brayden still) ((Praying so.. he deserves that chance and so do you)) We have made many advances and still are for alternatives for our kids #LivingBeyondACure Unfortunately too may have passed already. You my friend, we will always have our friendship and continue to fight to give our children the best we can! With Team Sanfilippo and our true comrades we will never be alone in the fight!

Carl, I am at a loss for the right words. I fall short. Losing a child is so hard. One thing that helps is not having any regrets. You have done everything you could do. THE boys have you love.

Joe Clifford